Join The Global FoodBanking Network on a journey around the world and explore how food banks are an often-unseen solution to reducing food loss and waste and getting nutritious, fresh food to people facing hunger, and so much more.

Ghana

Food for All Africa’s Agricultural Recovery Project Builds Bridges That Alleviate Hunger and Unite Communities

By Jason Woods

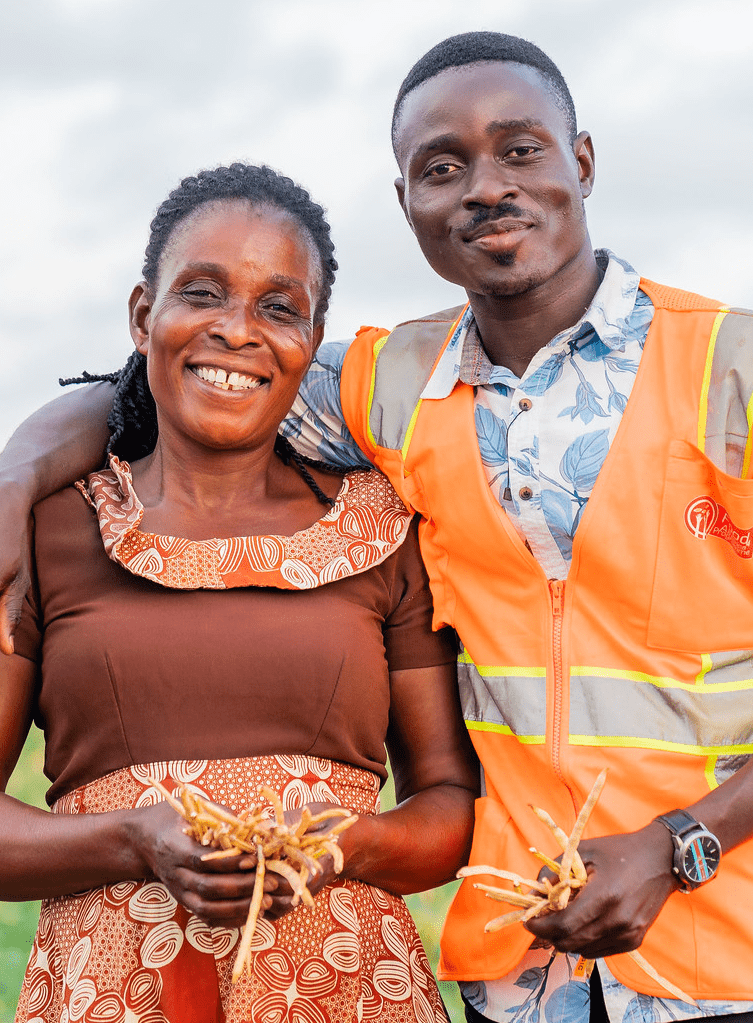

On a warm, cloudy day in Ghana’s coastal savanna, Isaac Agbovie expertly navigates the dips and divots of a rural road atop a slender motorcycle. He’s on his way to meet his mother at her farm, but when he arrives there’s little time for pleasantries. For Agbovie, who is wearing a bright orange vest with the word “staff” on the back, this is a work trip, and he quickly begins to help her harvest watermelons and green beans and place them in crates.

Hired in July 2023, Agbovie is one of five field coordinators employed by Food for All Africa, one of the first food banks established in West Africa. The new employees are one part of the food bank’s strategy to improve the nutritional content of the food they regularly provide to people facing hunger.

Agbovie’s mother, Victoria, has been giving produce to Food for All Africa since April 2023, and it was her idea for her son to apply for the job in the first place. Now he spends his days building relationships with both small- and large-scale farmers in the community where he grew up and beyond, all in the name of getting food to the people who need it most.

“What I learned from my mom is that you need to always give to people who need it, and that’s what my mom has been doing,” Agbvoie said, “And since I met an organization that is doing that, I’ve loved working for them. That’s why I go to faraway places, to search for food that would have gone to waste for us to recover and then use to feed the vulnerable.”

When farmers in the Greater Accra region know they have fresh produce that would otherwise go to waste, they call Agbovie. This happens for a variety of reasons. Sometimes crops yield more than expected regionally and small-scale farmers have a hard time selling the produce due to low demand. Other times, the size of the produce might not fit buyers’ expectations — something farmers here say is happening more and more due to climatic changes in rain patterns. In exchange for the produce, Food for All Africa provides training on topics the farmers are interested in, like establishing irrigation to adapt to unpredictable rainfall. In the future, the food bank wants to help farmers extend the life of their produce by offering low-cost cold storage rental.

Because produce perishes quickly, the logistics of recovery must also happen quickly. Agbovie recruits local volunteers to help harvest, thanking them with a hearty lunch, and arranges for a Food for All Africa refrigerated truck to load up the day’s haul and head to a warehouse in Shai Hills, about an hour away. There, a team of seven staffers unloads the watermelons and other produce, which is properly received, cleaned, and sorted before it’s stored. Some of the produce might be made into juice and frozen, but the rest of it will be packed for distribution.

“I appreciate a field coordinator’s job so much,” said Elijah Amoo Addo, founder and executive director of Food for All Africa. “When Isaac joined the team, our kilograms recovered immediately started increasing. He actually puts pressure on us to recover more and more produce.”

According to Addo, a culinary expert affectionately referred to as “Chef Elijah” by his team, about 45 percent of the food produced in Ghana goes to waste, while about 40 percent of children in the country go hungry. Determined to turn this around, Addo and his team at Food for All Africa created the Agricultural Food Loss Recovery Project in 2022 to reduce food loss in Ghana’s agricultural sector by 40 percent in the next five years. The fruits and vegetables recovered from the project are distributed through the food bank’s Lunch Box school feeding program and other initiatives that provide food to people in vulnerable situations.

In 2023, Food for All Africa put much of their focus into agricultural recovery, starting with the hire of the five field coordinators. Funding from The Rockefeller Foundation and The Global FoodBanking Network accelerated the program’s growth, allowing for the purchase of two all-terrain cycles so field coordinators can access hard-to-reach communities as well as the 1.4-ton capacity refrigerated truck. The funding also led to the creation of the Shai Hills warehouse, which was inaugurated in October 2023. The facility’s colorful exterior, adorned with photos of people enjoying fresh fruits and vegetables, explains the building’s purpose well. It can store up to 325 tons of produce and hold 56 tons of dried food like rice, gari, black-eyed peas, and soya. Previously, the food bank mainly relied on their satellite warehouse in Kumasi, three hours away from Accra, which holds 30 tons of fruits and vegetables in cold storage and 20 tons of dried food.

More storage that adheres to the highest safety standards, specialized employees, stronger connections to farmers, and a focus on agricultural recovery has transformed the way Food for All Africa operates. In 2022, less than 1 percent of the food they recovered came directly from farms. Just a year later, 28 percent of their food was sourced from the agricultural supply chain.

“Since we received the funding, it ignited a light for us,” said Addo. “We’ve been able to provide a more nutritious, health-focused support system to those we serve. And it also helps reduce food loss and waste. Above all, it helps us support malnourished families and children.”

Only a day after Agbovie and his volunteer crew loaded watermelons onto the refrigerated truck, the fruits are driven from Shai Hills to the Ansaar Foundation School in Ashaiman, one of Greater Accra’s lowest-income urban areas. The Food for All Africa staff members are given a warm welcome from Fati Abdulah, a teacher who helped start the school’s relationship with the food bank.

Established in 2013, Ansaar initially offered only Arabic classes in a humble wooden structure surrounded by the harried movement of the working-class neighborhood. “As time went on, we got to know that a lot of kids were roaming about with no school,” Abdulah said. So school officials decided to expand Ansaar’s offerings to provide a full curriculum and meet the needs of families in the community. The school now serves 194 students, ages 1 to 14.

In 2020, Ansaar became a part of Food for All Africa’s Lunch Box program, which every month provides enough food for daily lunches and snacks for 25 schools in Ghana. Food for All Africa also connected Ansaar directly with a donor that completely rebuilt the school, which now includes a kitchen where staff can prep and cook meals.

Abdulah leads the Food for All Africa staff members into the school and up a winding staircase to the top floor, where buoyant children fill six separate classrooms. When they see the watermelons, frenetic energy takes over in the youngest students, and the all the teachers pause their lessons for snack time. It’s hard to hear Abdulah speak over the laughter.

“[Programs like these] push for more education in a community like ours, where a lot are very vulnerable, poor,” Abdulah said. “It’s not easy. It’s a time where food in Ghana is very expensive. The food encourages the kids to come to school. They know when they come to school, they have something to eat.

“We feel amazed,” she added. “We feel we’ve gotten a helper, a supporter. That’s how we feel right now because [Food for All Africa has] really been doing a lot.”

On another day, Addo and his staff are again on the backroads of the coastal savanna, traveling to another farm. Addo is driving and one of his colleagues, seeing a large depression in front of them, says, “Chef, be careful, it’s deep!” Addo replies, “It is deep, but we keep going.” And they do, arriving at their destination safely, ready to restart the process of connecting farmers and food systems to hundreds of organizations like Ansaar Foundation School that are committed to making their communities better.

“You know,” Addo said, “there’s a saying that goes, ‘A problem half-shared is a problem half-solved.’

“For us as food bankers, we understand that what we offer is more than food. We become a bridge. The language we’re using is the food. But the identity we’re building is community. And for me, that’s the beauty of food banking.”

Guatemala

The expansion of Desarrollo en Movimiento’s warehouse in Guatemala City means they can recover more wholesome food and get it to those who need it most.

By Alice Driver

At a warehouse in Guatemala City, a group gathers at dawn to load food kits into a truck as the sun rises. They are all volunteers, including Mirthala Reyes, 69, a cancer patient, united in the mission of the Desarrollo en Movimiento food bank: to nourish their fellow Guatemalans while reducing food loss waste.

This morning’s shipment of 1,000 food kits – filled with fresh fruits and vegetables and staples like rice and beans – is destined for a group of widows and single mothers in El Rancho, a town of 8,000 about three hours from the capital on winding mountain roads.

In Guatemala, where 45 percent of the country faces food insecurity and half of all children face chronic malnutrition, Desarrollo en Movimiento strives not just to provide food but nutrition, including recipes and cooking classes for recipients. Between 2018 and 2023, Desarrollo en Movimiento donated over 15 million pounds (7.1 million kilograms) of food to low-income families and individuals.

“We take advantage of food that would be wasted or thrown away to improve nutrition and health,” said Juan Pablo Ruano, the director of Desarrollo en Movimiento.

The food bank relies partially on donations from farmers and companies like Walmart Mexico and Central America and Ducal to source fresh produce. And local farmers donate to the food bank as well; for example, lettuce, okra, or other vegetables and fruits that don’t meet the strict standards of supermarket shelves. Last year, they recovered 1,300 tons of fruits and vegetables from farms, which enabled them to serve 63,000 per month. It also means Desarrollo en Movimiento contributes to a more sustainable food system that addresses climate change by reducing food waste.

Through a grant from The Rockefeller Foundation to The Global FoodBanking Network, which partners with Desarrollo en Movimiento, the food bank has been able to put even more focus on improving nutrition for those facing hunger. That funding helped the food bank buy more racking and expand food storage capacity at its warehouse by 52 percent, which allows an extra 225 tons of food to be stored before being distributed to communities across the country. It also purchased another truck to transport farm surplus, expanding their capacity to recover fresh produce by 35 percent.

In the town of El Rancho, Clara Luz Ruano, 61, sits in the late morning sunlight beside her granddaughter Michelle, her long, dark hair braided, waiting to receive a food kit. Like many women present, Ruano says she is here for her grandchildren. Three of them live with her, and with food prices rising, she worried about providing nutritious food for them.

Near Ruano, Ruth López, 27, a mother of two, stood cradling her three-month-old daughter Catalina. “I want to make sure my kids eat healthy,” she said. Since her husband lost his job, they have had trouble making ends meet and hope the food kit could help keep the family nourished.

Inside her home, Nora Martiza Cruz Coronado, 51, opens the kit and places bags of rice, beans, cooking oil, fresh vegetables, and bananas on her table.

“I’m going to make meals for my grandchildren,” she said, standing barefoot on the dirt floor of her home, as chickens and geese walk in and out. Cruz Coronado, a street vendor who lives in El Rancho, is one of over 50,000 underserved Guatemalans to receive donations from Desarrollo en Movimiento in December 2023.

To make the most of the food kits, Sofia Aguilar, the nutritional and social management coordinator at Desarrollo en Movimiento, develops recipes like okra stew since many Guatemalans aren’t used to eating okra. Aguilar also develops popular recipes like chocolate cake made with bananas, teaching the recipients of donations how to make more nutritious versions of their favorite foods.

“Mothers bring their children [to our cooking classes], and they can try new foods and realize that they are delicious,” said Aguilar. “We want to create a workshop for the children to get them involved in food preparation.”

At her home in El Rancho, Cruz Coronado says she hopes to participate in the cooking and nutrition classes offered by Desarrollo en Movimiento so she can make the most out of every meal. She cares for her son Oscar, who was injured in a motorbike accident that broke his pelvis; her daughter-in-law Lesly; and her grandchildren Emma and Eduard.

“It has been hard because he is still recovering,” says Cruz Coronado of her son. She is currently the sole breadwinner in her house and times are tight. “I thank God because this helps us a lot,” she said of the food kit. “Prices keep rising, and I’m thankful for this food.”

Honduras

Despite myriad logistical challenges, Banco de Alimentos de Honduras is committed to getting fresh produce to those who need it most.

By Alice Driver

To reach Pilones y Flores de Honduras, a family farm outside of Tegucigalpa, Adrián Yaddy Torres Zavala must navigate dirt roads overrun by rivers. But it’s a drive he and a group of volunteers from Banco de Alimentos Honduras enthusiastically do whenever they get the call.

“Our employees call Adrián and tell him that next week we will have X quantity of lettuce or cucumbers for them to collect,” said Ricardo Bulnes, the owner of the farm. Because of strict aesthetic standards at supermarkets, Bulnes isn’t able to sell everything the farm produces so he ends up with a surplus of fresh lettuce, tomatoes, and other vegetables.

But just over a year ago, Torres Zavala, the program coordinator for agricultural recovery at the Banco de Alimentos de Honduras, showed up at the farm and told Bulnes he had a solution for that extra produce that helped people and the planet. Instead of letting it rot in field or a landfill and emit greenhouse gases, Banco de Alimentos de Honduras would come harvest and collect the produce and then deliver it to Hondurans facing food insecurity.

As he walks through the expansive greenhouses on the property, Bulnes laments watching good food go to waste. Fresh produce is such a blessing, something he sees every time his grandchildren visit the farm and eat lettuce leaves straight from the greenhouse.

Bulnes says he knows how important it is to keep produce from ending up in landfills, where it produces methane and contributes to climate change. Globally, wasted food is responsible for 8 to 10 percent of greenhouse gas emissions.

Bulnes points across the farm, showing a right arm marked by a deep, ragged scar left by a rattlesnake bite. Since this family farm opened in 2006, he has witnessed the impact of climate change on the Honduran countryside.

“Like everyone, we have been impacted by climate change,” he said, explaining how a river had overtaken the road where trucks used to arrive to load his produce to be sent to markets. “In this area, we have been affected by rain and the quantity of water that falls quickly. The effects of climate change are more dramatic every year.”

Walking toward the river, Bulnes arrives at a cable ferry, which he had made in a pinch when he needed to get vegetables across the river after a hard rain.

He is thankful that Torres Zavala and Banco de Alimentos de Honduras make the difficult drive to the farm to recover the fresh produce. Thanks in large part to a grant from The Rockefeller Foundation to The Global FoodBanking Network, which counts the Honduras food bank as a member, it’s just one of many farms in Honduras no longer wasting surplus produce. Banco de Alimentos de Honduras has been able to connect with many farmers and increase its capacity to recover fresh produce. Last year, Banco de Alimentos de Honduras recovered over 154,000 kilograms of food from farms like the one Bulnes runs, as well as corporations like Walmart. That same year, the food bank served 36,512 people.

“To send fresh vegetables that would otherwise go to waste to families in need is a beautiful thing,” said Bulnes.

Reaching Berlín – an impoverished neighborhood in the hills above the Honduran capital – is an entirely different transportation challenge for Torres Zavala. The only ways in are steep, narrow, dirt-packed streets. He’s hoping they can get their truck filled with vegetables from Bulnes’ farm up the hills before the afternoon rain, which would make driving treacherous.

Today, they make it safely. As volunteers unload the truck, Torres Zavala stands with María Cristian Bacedano, 55, the community leader in Berlín who helped coordinate the food delivery, and marvels at the seemingly never-ending slope up which the neighborhood stretches. He says produce like this doesn’t often reach these marginalized communities, where families not only struggle against poverty but also entrenched gang violence.

People here “don’t consume fresh fruits and vegetables as much, so we want to support them so they get used to such staples,” he says, especially now as they are able to source more through agricultural recovery work.

Bacedano helped organize food basket donations for 179 families in the community, and alongside Banco de Alimentos Honduras, was also coordinating cooking workshops and recipes so families could maximize the nutrition they get from their fresh produce.

Rosa Evangelista Mendoza Galindo, 53, stood among the crowd of women and children, waiting to receive bananas, potatoes, onions, and lettuce. A single mother of five, she was thankful to be able to prepare meals from wholesome ingredients.

“These are people with few economic resources who can’t get what they need from supermarkets,” Bacedano said. “These are the people we search for, people who don’t have stable jobs and who will benefit from this food.”

Kenya

Food Banking Kenya's Produce Depot Helps Small-Scale Farmers Get Value for Their Surplus While Getting Food to Those Who Need It

By Chris Costanzo

Just off a main road well north of Nairobi, in the foothills of the Aberdare Mountains, low-slung cinder-block buildings eye each other across a broad dirt lane. Flags atop two spindly tree-trunked poles indicate that this is a site of government activity – the local police station and a county administrative office are located here.

As a village elder in Kamae, the hamlet just down the slope, Robert Chege has been a familiar presence at this site for years, representing the interests of his fellow farmers and villagers in government decision-making. Energetic and charming, Chege – nicknamed Tronic for the small electronics shop he also runs – is a man whom everyone in town knows and trusts.

Not long ago, Chege embraced a new voluntary role in the community: He helps hundreds of small-scale farmers throughout the surrounding area to offload surplus produce they can’t eat or sell, while gaining access to foods they otherwise wouldn’t be able to obtain.

Food Banking Kenya brokers this exchange, working through a facility it built that sits alongside the government buildings and is known locally as the produce depot. The depot addresses a cruel irony of food insecurity: while there is enough food to feed everyone, it’s not always available in places where the people who need it can get it. In Kenya, for example, 40 percent of the food produced – worth $655 million – is wasted each year, as about 37 percent of the population goes food insecure.

In a place like Kamae where most everyone has a small plot of land to cultivate, certain types of food are almost always in abundance, like the cabbage, kale, and potatoes that grow well in the area’s cool climate. At the depot, Chege takes in donations of this surplus food, recording them in a small notebook, as villagers arrive with bundles of food carried on their backs, bikes, motorcycles, wheelbarrows, and donkeys. On a recent day in January, he documented six donations, including one of 140 pounds (64 kilograms) of cabbage and another of 33 pounds (15 kilograms) of potatoes. Day after day, the donations add up.

A couple of times a week, Food Banking Kenya sends a vehicle up to this mountainous region to collect all the food that Chege has gathered and bring it back to Nairobi where food insecurity is acute and the fresh produce can go to good use. At the same time, the food bank drops off items that Chege’s fellow farmers could use, like rice, cooking oil and flour, or vegetables that are not easily grown in the region, such as squash or maize.

The scene at the produce depot is a microcosm of a scenario that plays out along the farming supply chain all over Africa and the world. Globally, between 33 percent and 40 percent of all food is wasted as it moves from farm to fork. Of that, about 15 percent is lost on farms during and after harvests. “Food is in plenty here,” Chege said, describing the fertile region where he lives. The produce depot “is a place where we can take the food so that it can help people instead of going bad.”

The produce depot in Kamae, shaped like a small shipping container, has become a blueprint for three others Food Banking Kenya has since built, and it wants to build more. A grant from The Rockefeller Foundation to The Global FoodBanking Network to support 13 food banks in ten countries across Africa, Asia, and Latin America will help Food Banking Kenya construct its next depot.

Through the grant funding, which overall aims to address food insecurity and reduce food waste, Food Banking Kenya is also expanding its ability to store and transport produce. It has purchased a refrigerated van, added refrigeration to an existing van, and added a chest freezer to its warehouse to store protein recovered from retailers. It has also built a solar dehydrator near the Kamae depot to dry out fresh produce, making it easier to store and transport while still retaining its nutrient density. So far, the funding has helped the food bank increase its agricultural recovery by 79 percent.

Such capacity building is necessary, especially because the food bank also has relationships with large-scale growers and food packers who provide it with donations of surplus produce, up to six tons at a time. All in all, agricultural recovery makes up more than 90 percent of the food bank’s sourcing, an approach that helps reduce food waste and its contribution to greenhouse gas emissions, while also providing nutritious food to people who need it. Eighty percent of the food bank’s distributions go to children, with the remaining going to the elderly.

While infrastructure is critical for handling produce, Chege has proven that a personal touch is paramount when it comes to sourcing. Harnessing the power of a network, Chege has trained about 10 other farmers throughout the county to also mobilize farmers in their areas to contribute surplus produce. His efforts have helped expand the number of small-scale farmers contributing to the produce depot from 200 to 600. “I use a motorbike or a bicycle,” Chege said. “That’s what I use to spread the information. I talk to them on the farms and tell them all to come.”

The food bank’s network of small-scale farmers is set to expand even further as it amplifies Chege’s method of grassroots outreach. It has already identified another farmer in a neighboring county whom it hopes will be as impactful as Chege in marshaling local farmers to donate their surplus produce. “We’ve seen that having a farmer actually go around and talk to the others has proven to be very effective,” said John Gathungu, co-founder and executive director of Food Banking Kenya.

Gathungu planted the seed of this still-expanding network back in 2016 when he noticed an imbalance between the hunger he witnessed in Nairobi, where he had moved as a young adult, and the bounty of produce he knew existed in the mountainous region near Chege’s village, where Gathungu’s parents owned property. An overabundance of carrots at his parents’ house one day prompted him to bring a supply of the vegetable back to Nairobi, to share with his city neighbors. Soon, the vegetable transports were becoming more frequent, and the distributions more formal. Gathungu was running a food bank without really knowing it.

Now Food Banking Kenya serves tens of thousands of school children through relationships with more than 50 organizations including schools and orphanages. In 2023, it distributed nearly 635,849 kilograms of food throughout 13 counties, serving 66,000 people. Its membership in The Global FoodBanking Network has helped Food Banking Kenya gain technical assistance and knowledge. It was through a visit last year with Leket Israel, a fellow member of The Global FoodBanking Network member, that Gathungu observed the importance of nurturing close relationships with a vast community of farmers. “I realized this was an approach we could use,” he said.

On a recent Friday at the food bank’s warehouse, various organizations arrived to pick up food to take back and distribute to the people they serve. Margaret Nekesa, the founder and director of Smile Community Centre, which houses 80 orphaned and vulnerable children in southeastern Nairobi, had rented a car to transport all the food she would receive to take back to her charity.

It did not seem possible that the towering crates of fresh produce that were wheeled out of the food bank’s cooler would fit into the car. It was a modestly sized car, and the columns of fresh produce, some of it retrieved just the day before from the depot, stretched high above everyone’s heads. But little by little, all the produce was transferred into large, nearly bursting mesh bags that were then loaded into the vehicle.

By the end of the day, the large cooler was empty and all the produce was out in the community. That’s just the way Gathungu likes it, to be ready for the next cycle of agriculture recovery and redistribution that would start again on Monday.

Nigeria

Lagos Food Bank Initiative’s Agricultural Recovery Program Advances Nutritional Health

By Chris Costanzo

Sunday Olufemi has been earning money from farming since he was about 5 years old. He started out helping clear weeds from a neighbor’s local gas station, using the money he earned to plow about a half-acre of land in his backyard for cassava and maize. From there, his farm work and his passion grew.

“Farming has become a part of me,” he said.

Now Olufemi is the manager of one of Fempanath Nigeria’s two large farms, this one located about two hours north of Lagos, Nigeria. At this location, Fempanath grows mostly citrus fruits like oranges and tangerines and some vegetables, including tomatoes and cucumbers, on about 150 acres of land. It uses a drip irrigation system to keep its plants hydrated, and like most farms, it has big issues when it comes to surplus produce.

“Food surplus has been a major challenge for farmers in Nigeria, especially here in the South West because of our long rainy season,” Olufemi said.

During the rainy season – when there’s no need for irrigation – backyard farmers throughout the area start planting, depressing the local market for produce and leading to excess. Olufemi estimates that about 50 percent of the farm’s production during the rainy season is surplus.

Now the farm has a new outlet for its extra produce. On a recent Monday, an enthusiastic group of volunteers from Lagos Food Bank Initiative (LFBI) fanned out across the farm, gathering up about 40 crates of sweet oranges that had already fallen from the trees and were at risk of deteriorating. The fruit filled a van that carried it all back by nightfall to the food bank’s warehouse, where it would be stored until it could be distributed to under-resourced communities throughout Lagos, the largest city on the continent.

“When we have surplus, the food bank will come and take it,” Olufemi said. “It’s a great advantage for us.”

Food surplus may be prevalent, but it is devastating when examined through the lens of food insecurity. In Nigeria, Africa’s largest economy with a gross domestic product of $44 billion, 116 million people — or 44 percent of the population — are moderately to severely food-insecure. At the same time, about 40 percent of all the food produced in the country is lost after harvest.

LFBI is addressing this imbalance by taking on the logistical challenge of redirecting surplus produce to people who need it. Its agricultural recovery program also keeps food from ending up in landfills, helping to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

But there’s a lot that needs to happen behind the scenes for the program to be successful. Fresh produce requires a cold supply chain, careful handling, and speedy distribution to ensure it doesn’t go bad. LFBI is addressing these needs by tapping some of the $2.8 million of funding that The Rockefeller Foundation allocated last year through The Global FoodBanking Network, of which LFBI is a member, to help 13 food banks in 10 countries across Africa, Asia, and Latin America address food insecurity and food waste.

With the funding, LFBI is adding a cold storage room to its warehouse to keep the produce fresh until it can be distributed, as well as solar-powered electricity and a backup generator to support it. Extra racking to store the produce is also necessary, as is a refrigerated van to transport it.

Michael A. Sunbola, president and executive director of LFBI, said he expects to collect about 3,000 to 4,000 pounds of fresh produce (about 1,500 to 2,000 kilograms) for every trip the food bank makes to recover surplus produce. “With the funding, we will be able to recover much more than what we’re currently recovering,” he said.

Adebisi Adedeji, a former farm manager, is spearheading the food bank’s new agricultural recovery program and identifies new potential farm partners. By early 2024, the food bank already had half a dozen or so partners and was expecting to add many more. “We want to recover as much produce as possible,” Adedeji said.

Challenges remain, including a highly unreliable road network. Fempanath’s farm, for example, lies about a mile from a main road, along a heavily potholed dirt pathway with peaks and valleys that can turn into a muddy mess during the rainy season. Even so, Adedeji hopes to make recoveries at this farm and others on a weekly basis.

Agricultural recovery is the newest program at LFBI, an organization that is itself relatively new, having formed in 2016 at a time when food banking was a novel concept in Nigeria. “There was no such thing as a food bank when we started,” Sunbola said. “No one was thinking about food.”

Sunbola, however, was thinking about it a lot. He had begun practicing as a lawyer in 2009, but memories of his early childhood kept tugging him in another direction. “Most of my memories of childhood are of not having enough food to eat,” he said, recalling going to bed hungry and to school hungry. “It is not a pleasant memory.”

Starting at age 6, he began fending for himself and his four siblings, running small errands to pick up spare change for food. Eventually, his family’s finances improved, giving him the ability to attend law school. But the memories of his hungry childhood would not go away. “I thought, ‘Why is this still coming back to me?’”

So he turned to the internet, using “food foundation” as his first Google search. That brought him to “food bank,” and specifically the Houston Food Bank in the United States. “I thought, ‘This is it. This is the model.’”

Sunbola initially used his own resources to support his fledgling food bank, sometimes heading to the market in his suit and tie after work to purchase dry goods or ingredients for prepared meals. LFBI eventually gained outside support and now operates in 160 communities and has reached 2.4 million people through nine programs.

With so many programs, the produce that the food bank recovers hardly has time to sit on a shelf before it is distributed. The produce collected from Fempanath’s farm, for example, found its way the very next day into the hands of hundreds of community members.

On that morning, LFBI hosted about 30 mothers and their infant-to-toddler children at its warehouse as part of a program that seeks to address Nigeria’s high rate of infant and maternal malnutrition. One of the moms, Toyin Koleosho, was pleased to report that her daughter Angel had benefited greatly from the nutritious food provided by the food bank every two weeks over the course of a few months.

Angel had been referred to the program by a local primary healthcare center — LFBI has relationships with 42 of them in Lagos — for being underweight. At 4 months, the baby was only 6 pounds (2.8 kilograms), but over the course of the program, “her body changed,” reported Toyin. “Now she moves more, and she has a big smile.” At 9 months, Angel weighs a much more age-appropriate 17 pounds (7.8 kilograms).

The moms in the morning program received citrus from the Fempanath farm, with the remainder loaded up in the afternoon for distribution to a fishing community on an island off of coastal Lagos. Volunteers helped move hundreds of boxes of food and accompanying bags of produce by truck and then boat to the fishing village. With “the fish not coming like before,” Juliet Akwa, one of the recipients, expressed her happiness at receiving the food staples and produce for her two children, a boy and a girl, aged 3 and 7.

The moms in the morning program received citrus from the Fempanath farm, with the remainder loaded up in the afternoon for distribution to a fishing community on an island off of coastal Lagos. Volunteers helped move hundreds of boxes of food and accompanying bags of produce by truck and then boat to the fishing village. With “the fish not coming like before,” Juliet Akwa, one of the recipients, expressed her happiness at receiving the food staples and produce for her two children, a boy and a girl, aged 3 and 7.

While produce recovery from farms offers all the satisfying benefits of reducing waste and simultaneously addressing food insecurity, Olufemi of Fempanath underscored perhaps the biggest upside to putting nutritious fresh food into the hands of people in vulnerable situations. It has to do with food being “an essential aspect of life,” he said. “There is a saying,” he noted, “that you ought to be paying farmers, not your doctor. Your food is your health.”

phillippines

Rise Against Hunger Philippines’ innovative idea makes sure nutritious food doesn't go to waste and farmers get the most for their surplus.

By Micaela Wu

When a research study found that about half the excess produce at one of the largest agricultural trading posts in the Philippines was going to waste, a local food bank was ready to rise to the challenge.

Although it’s a seven-hour drive to Nueva Vizcaya from metro Manila, Rise Against Hunger Philippines (RAHP) soon found themselves making regular visits to Nueva Vizcaya Agricultural Terminal (NVAT), a public-private joint venture where thousands of farmers go daily to sell the produce that supplies much of the mainland’s major markets. With an opportunity to recover produce at this critical point of the food supply chain, RAHP developed a unique program that gives farmers a hand while bolstering the nutrition and food security of local communities: a food bank where farmers can trade in their surplus produce in exchange for shelf-stable goods and essential supplies.

Inside the gates of the terminal, food is in abundance. From sunrise to well past sundown, men unload vehicle after vehicle full of cabbages, crates of cauliflower, and huge plastic sacks full of gourds, ginger, and long beans, perfectly arranged. But a significant amount of the produce farmers bring does not get sold, meaning that food does not make it to retail markets, nor end up on people’s plates. Sometimes, fruits and vegetables can’t be sold because of cosmetic imperfections, like not being the right size or color, or other imperfections like insect bites or blemishes accrued during handling. But, even if the produce does look perfect, the aesthetic appeal and uniformity of the product doesn’t always guarantee that it will be purchased by a buyer. If everyone is trying to sell tomatoes, for example, it might be difficult to sell everything if a farmer has a huge supply. Additionally, the price that buyers offer in times of bounty will be low, so it might not even be worth for farmers to pay for transportation to the market in the first place. All these cases have traditionally led to wasted food.

Rodolfo Eugenio Valdez has been working at NVAT since 2010 as a trader and grows crops on the side. When asked how often he’s had to throw away produce in the past, he said, “When business is slow, some of it,” in his local dialect, Ilocano. Gesturing to the sacks of chayote, cabbage, and cauliflower in his tricycle, he added, “Because when prices are cheap and there’s over supply, we can hardly sell.”

There’s also a lot of hidden food loss that occurs at the farm before it gets to places like NVAT. Melania Runas, a 61-year-old farmer who has been selling at NVAT for decades, says that about 30 percent of her crops do not make it to the agricultural terminal, citing reasons like pest and plant disease, weather impacts, or overripening. Of the 70 percent that she can sell at the terminal, about 40 percent is very good quality and can be sold for premium prices, 15 percent for average prices, and 15 percent for low prices because they don’t meet cosmetic standards.

Recently, she had a lot of Chinese pechay, or cabbage, that she was not able to sell. “Our heart is crying,” she said. The cabbages were just the right size and the perfect shade of green, but they weren’t completely blemish-free. “We work hard and then we bring the produce to NVAT, and then [if we aren’t able to sell] we throw it away. There are many sacrifices there,” she said. “Or we can bring it to Rise Against Hunger Philippines and barter there. That’s why I’m very thankful for Rise Against Hunger Philippines, because if we cannot sell the pechay for the day, we can bring it to the [food bank].”

Tucked inside the back corner of the labyrinth that is NVAT, Rise Against Hunger Philippines has piloted a solution to recover the thousands of pounds of surplus food that may go to waste from farmers like Valdez and Runas. In contrast to the rows of incongruous stalls and pathways of the terminal, the food bank — a newly built warehouse with food items and essential supplies arranged neatly atop pristine shelves — turns the heads of curious agricultural workers who zoom by on their motorbikes. It is here that, at any odd hour of the day, farmers with surplus produce can arrive and trade their goods for those of the food bank.

Lauris Anudon manages the food bank at NVAT, overseeing the bartering and trading with farmers. When a farmer arrives, Anudon inspects the products and they agree on a value, in pesos per kilogram, usually after a little haggling. After the produce is weighed and a final peso value is determined, the farmer can select from a variety of products — including bags of rice, oil, tinned fish, instant coffee, noodles, and personal care products — that add up to the value of the produce they donated. Farmers walk away with products they would otherwise have to go out and purchase, and then the food bank is well stocked with all kinds of fresh produce to distribute to communities that are lacking.

“It’s a fair trade,” said Runas, when asked how she feels about her previous exchanges at the food bank. “Fair trade because it’s a barter system. I bring the Chinese pechay, and they bring me the rice and canned goods.”

In addition to maintaining the inventory at the warehouse, facilitating transactions with farmers, and conducting outreach about this program to others at NVAT, Anudon is also responsible for getting the produce that the food bank receives to people who could benefit, particularly school-aged children. In the mere 8 months that this program has been running, he’s already developed partnerships with 10 nearby elementary schools around Nueva Vizcaya. Anudon organizes weekly food distributions using the produce from the NVAT food bank, serving students from kindergarten to third grade, where class sizes can be up to three hundred.

“The bartered vegetables are given to the schools to support their school feeding programs,” Anudon explained. “In a way, it’s also an opportunity for the farmers to contribute to [community] development work. They are able to help feed schoolchildren who need to have better food so that they don’t go to their schools on a hungry stomach.”

For Rise Against Hunger Philippines, addressing child hunger is one of their highest organizational priorities. About 3 in 10 children in the country are undernourished, and approximately 95 children die every day due to malnutrition, according to research by UNICEF. So much of the food bank’s programming is focused on providing hot meals to schoolchildren and supporting organizations that run school feeding programs. School feeding programs not only support healthy growth and development at a critical period of life, but they can enhance academic performance, improve attendance, and incentivize children to stay in school long term.

“A sense of fulfillment that I get from this job is, we know that our school children are eating better food,” said Anudon, reflecting on all the logistics, coordination, and partnerships needed to make this work happen. “And I feel happy because we’re helping the farmers.”

Soon, the establishment of the food bank at the Nueva Vizcaya Agricultural Terminal will be approaching its one-year anniversary. Grant funding from The Rockefeller Foundation to The Global FoodBanking Network, of which RAHP is a member, kickstarted the project. Since receiving that funding, RAHP has already made a considerable impact in the community. And they’re just getting started.

“The ultimate goal of this agriculture recovery program is to reduce food waste, post-harvest losses, and in turn, donate those recovered vegetables to school programs where children are provided with fresh vegetables to bring home … and to reach the thousand farmers who are currently trading at NVAT,” said Jomar Fleras, executive director of Rise Against Hunger Philippines. He founded the organization in 2015 and is one of the masterminds behind the food bank’s innovative endeavors. “NVAT is the largest trading post in in the country, but there are several trading posts all over Luzon and other parts of the Philippines. I’m sure there’s a lot of food that can be recovered there. What we hope to do is to create a model that can be scaled up and replicated in these various trading posts.

“A whole community is being helped through this program,” Fleras continued, looking off in the distance toward the food bank and Anudon receiving another exchange of fresh vegetables from a farmer.

“I always tell people it takes a village to feed a child. And this is the village that we have created here in Nueva Vizcaya.”

Around the world, food banks are transforming recovered fruits and vegetables into so much more than food – they are creating healthier, more resilient communities.

Download the More Than Food recipe book to experience some of the special ingredients and dishes from the communities served by GFN member food banks.