Food banks respond to the needs of their communities, in whatever ways necessary—and that often means finding new and innovative ways to make sure everyone has food available.

In the last several years, some food banks are increasingly adopting a “virtual” model of food banking that connects organizations with surplus food directly to those nearby who need it. The model often takes advantage of existing technology to make those connections.

The Global FoodBanking Network (GFN) is currently evaluating the landscape of virtual food banking with an eye on helping interested members navigate through any challenges they might face. In the coming months, we will share more details on how we plan to do so. For now, let’s learn a bit more about the model.

What is virtual food banking?

Virtual food banking is also sometimes called “direct collection” because it allows people with surplus food to provide that food directly to either people facing hunger or the community agencies that distribute food.

In the most common model of food banking, the along the supply chain by collaborating with producers, processors and manufacturers, distributors, and retailers to identify what food is available. The food bank sorts, selects, and stores the food safely and then delivers that food to community service organizations that ensure it’s given to people who need it. In this way, food banks act as connectors, and they take on the responsibility of transportation and storage during the course of that service. That means food banks usually need a fleet of vehicles, warehouse space, and cold chain to operate.

A food bank using the virtual approach finds, through a variety of methods, those who have wholesome surplus food, then it lets those groups know which approved people or agencies are nearby and accepting food. In some cases, the company drops the food off, but in most cases, the community organization might pick the food up to distribute. In either case, food banks are again acting as connectors, identifying surplus food along the supply chain and working with organizations to provide that food to those who need it.

Both of these models effectively ensure that surplus food is delivered to people facing hunger are effective, but they do so in different ways. If food banks are the bridge between people who have surplus food and people who need that food, then virtual food banking can reduce the size of that bridge.

What are the benefits of virtual food banking work?

With fewer logistics issues, food banks might also be able to expand services more quickly to areas of high food insecurity that are difficult to travel to or far away. And a food bank that doesn’t have to concentrate on in-person collection, storage, and delivery frees up hours to devote to other activities, like dedicated hunger programs or finding even more partners who have surplus food to contribute.

If a food bank is connecting food donors to people or agencies that are close in proximity through virtual food banking, that might also cut down on overall fuel miles, which means fewer greenhouse gases produced through transportation. And that food might also get to where it’s needed a little bit more quickly since the distance traveled is shorter.

What kinds of technology are used in virtual food banking?

In the most basic cases, food banks can connect those with surplus food to those who need it through methods as simple as a phone tree or a shared spreadsheet. But in the last few years, food banks are increasingly using applications and other sophisticated technology to make these connections.

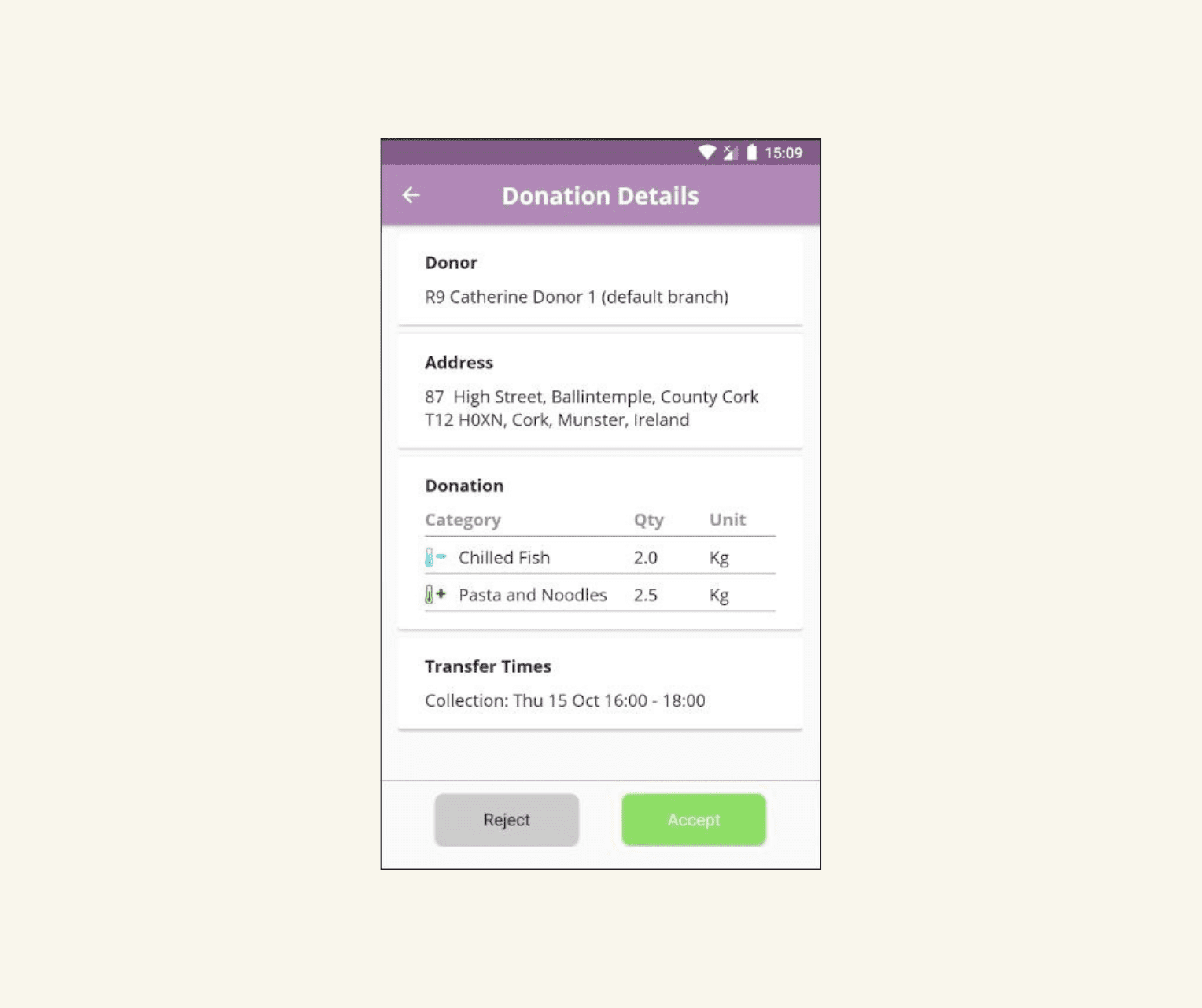

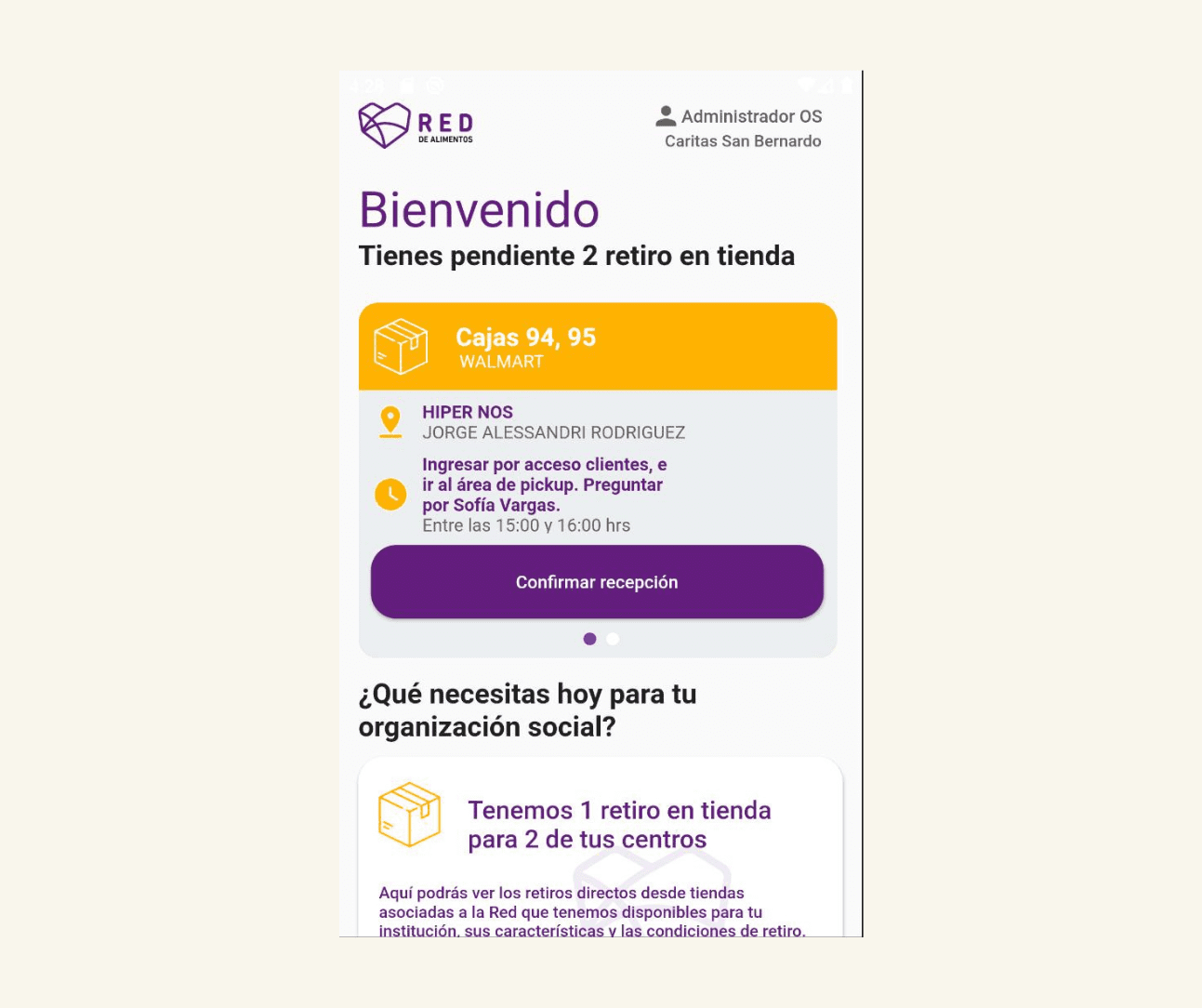

For example, a company might input the types and quantities of surplus food they have and when that food will be available into a virtual food banking app. The app can then take the information it has about participating community agencies—their operating hours, location, and programs available, as well as the number of people they serve and their ages—and notify them about the details of the food to be picked up nearby.

Where is virtual food banking currently in use?

Twenty food banks, or more than a third of GFN members, currently use virtual food banking—up from less than 5 percent just four years ago. In 2023, the amount of food GFN partners distributed using virtual food banking more than doubled, from 5 percent to 11 percent of all food distributed. In locations where these platforms are rolled out at scale, virtual food banking accounts for more than 35 percent of recovered food.

GFN member Red de Alimentos Chile is one of the early adopters of virtual food banking technology, as they created a system for retail recovery in 2010. But they actually shifted the focus of the app to recover agricultural produce in locations far away from their main location in Santiago. In 2022, the food bank organization provided 12 million kilograms of food to 262,000 people through virtual food banking. Likewise, GFN member FoodForward South Africa developed an SMS-based app at the end of 2016 to increase partnerships with food retailers.

Recently, GFN has partnered with FoodCloud, a Dublin-based food bank that has developed a virtual food banking platform used in Ireland, the United Kingdom, and Eastern Europe. This partnership is exploring the feasibility of using this technology to scale food recovery and redistribution efforts in sub-Saharan Africa and Southeast Asia.

Looking Ahead

In the coming years, the prevalence and role of virtual food banking is only likely to increase, and GFN is committed to helping member food banks navigate this emerging model. We’re currently developing a technology road map that details current operating models, and interested food banking organizations will be able to use this tool to begin recovering food using a virtual supply chain. And we’ll continue to monitor the landscape of virtual food banking to ensure that food banks around the world have the resources they need to respond efficiently and effectively to the needs of their communities.