Banque Alimentaire de Madagascar’s critical role in strengthening local food systems in the midst of climate change has never been more apparent for Ieja Ranaivoniarivo, the food bank’s partnership development manager. She has been with the food bank since its inception in 2018, the same year that severe droughts started afflicting the southern part of the country—droughts that still persist to this day. As a result, the number of people facing food insecurity in Madagascar has grown dramatically to over 8.8 million people, or about one third of the population. Last year, the World Food Programme stated that these droughts could be considered the first climate-induced famine in the world.

Madagascar is more vulnerable to climate change than most countries, and it’s one of the least able to adapt to these shocks due to its geographic location and limited economic and development capacity. The country’s susceptibility to climate change has led to drought, cyclones, and other unpredictable weather patterns that have severely affected food production. Because most of the population depends on agriculture for their livelihoods, disruptions in this sector have significant effects on food security and the economy. High rates of poverty limit access to nutritious food for many households, and rapid population growth and limited infrastructure further exacerbate the situation, making it even more difficult to access food and essential supplies.

“The inception of the food bank in late 2018 was driven by the necessity to address climatic disruptions in Madagascar,” said Ranaivoniarivo. “We contacted GFN in 2019 to receive guidance on the necessary steps for establishing Banque Alimentaire de Madagascar. As we were identifying pilot areas to establish the food bank, we had to take into consideration regions prone to climatic hazards like cyclones, floods, and drought.” The food bank soon joined GFN’s Incubator Program, now known as the Accelerator Program, in late 2019 to build capacity and strengthen operations., But a few months later, the pandemic hit.

Food banks all around the world, and particularly in areas with already acute rates of food insecurity like Madagascar, felt the weight of increased demands for food amid the economic impacts, supply chain disruptions, and public health hazards brought on by COVID-19. Not only this, but the drought in southern Madagascar had worsened in mid-2021, causing an estimated 1 million people to be pushed into food insecurity.

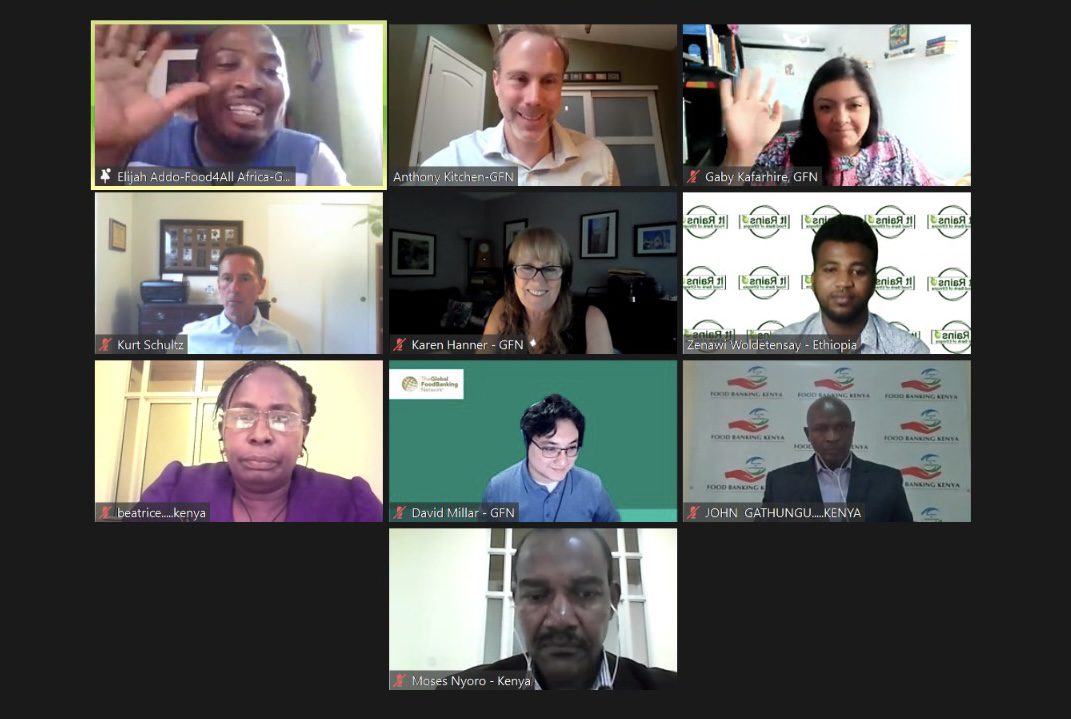

“We worked tirelessly with Banque Alimentaire de Madagascar to provide technical assistance and moral support during this time,” said Gaby Kafarhire, GFN’s Africa and Middle East programs associate director. “It’s amazing that they could develop and build capacity over these two years.”

The food bank worked with GFN’s Programs team to draft infrastructure plans and workplans in three new locations in Ambohimalaza, Amboasary, and Farafangana. GFN also supported Banque Alimentaire de Madagascar during their lengthy process to become a registered nongovernmental organization in the country in order to receive funding from local and international partners, including GFN. During this time, they also further developed special programs like an agricultural recovery partnership with small-scale farmers.

In May of this year, nearly four years after GFN’s first initial visit to Banque Alimentaire de Madagascar, Kafarhire, along with Accelerator Program Coordinator Mohama Tchatagba, were finally able to visit the food bank and witness the progress made during a tremendously difficult time and collaborate strategically for the future. With climate change only worsening, countries like Madagascar are being forced to adapt—and this applies to the food bank too.

“During the trip, I visited a co-op of small-scale farmers that the food bank purchases food from,” said Tchatagba. “One of the major issues they experience is the impact of drought on their ability to produce crops like corn, sorghum, and beans. Rain is getting more infrequent, but when it does rain, it is more often coming in the form of cyclones that devastate farms and homes.”

The food bank is already strengthening the local food system in southern Madagascar by purchasing food from small-scale farmers and organizing training on sustainable land management. But without significant agricultural technology, production is limited. While the details are still in the works, Banque Alimentaire de Madagascar is looking into purchasing a tractor or milling machine to lease out to farmers, which would significantly improve their agricultural outputs, productivity, and efficiency or help extend the life of their food products. And in turn, the farmers would donate a portion of their crops or food products to improve local food security.

“These strategies are not just for the food bank’s benefit, but for the community’s benefit,” said Kafarhire. “In light of the climate change issues, poverty, and poor infrastructure, the food bank is trying to put together all these pieces. Banque Alimentaire de Madagascar doesn’t just operate a feeding program. They work across so many critical pieces to better livelihoods, including economic development and sustainable agriculture, so that things can improve for people’s daily lives.”